Empathy & Equity outlines historical and modern flaws that leave marginalized communities disproportionately vulnerable in the face of climate change. In highlighting healthier solutions, E&E weaves environmental justice into the fabric of the environmental movement to create a more equitable planet.

North Carolina’s hog industry is more empire than industry. With more factory-farmed pigs than people in the state, North Carolina is not only one of the largest pork producers in the nation, but in the world. Though this industry brings in approximately $10 billion in profit to the state, its costs to communities where these industrial hog farms are located are immeasurable.

The Impact is in the Numbers

North Carolina’s 9.5 billion hogs produce more than 10 billion gallons of waste each year, which is sprayed on fields as fertilizer. But before it is turned into something agriculturally useful, this waste is stored in lagoons, or expansive mounds of manure.

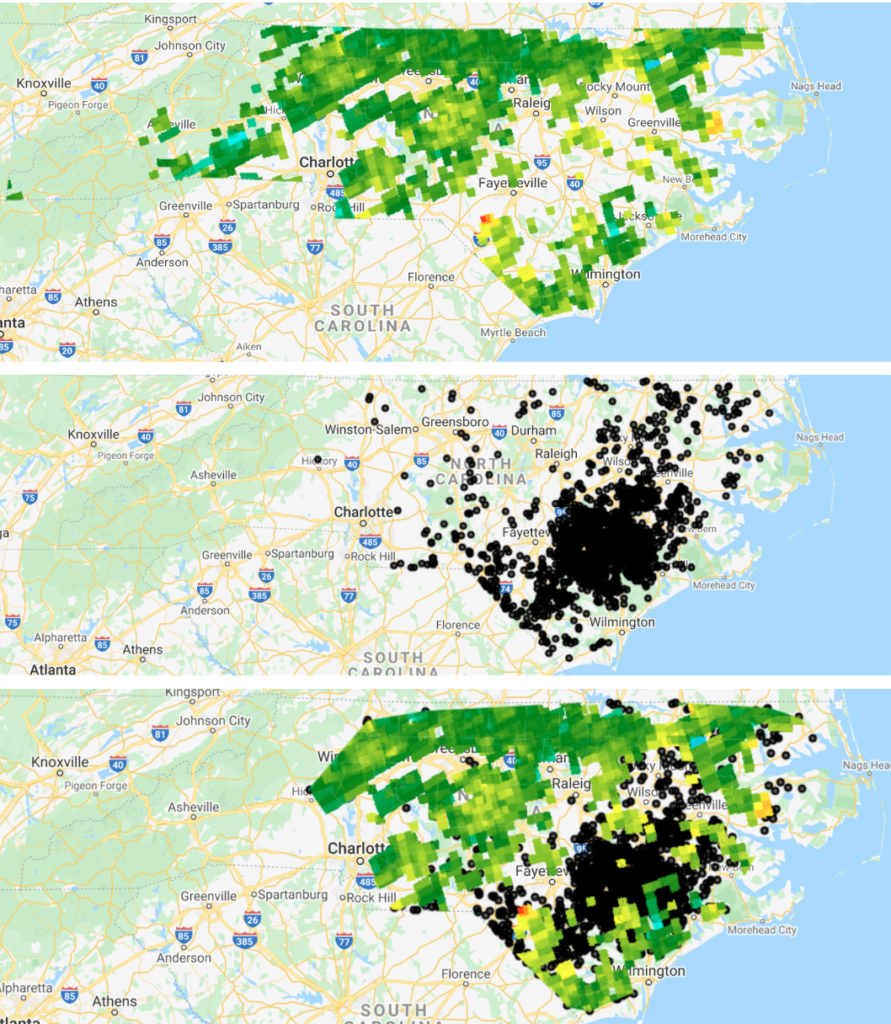

Manure lagoons cause numerous problems for communities with hog farms. One major issue is the massive amount of greenhouse gasses produced. The biogas that is released by these lagoons is 60 to 65 percent methane, a greenhouse gas that is 25 percent more insulating than carbon dioxide. The following maps show the location of the hog farms in North Carolina versus where there are the highest methane outputs.

These farms are mainly on North Carolina’s coast, where they are often battered by hurricanes and flooding. This poses another constant risk: Overflowing. Lagoon leakage contaminates local water sources and harms aquatic ecosystems, resulting in health complications like disease. After Hurricane Florence, more than 50 lagoons overflowed, with many others on the verge of spilling.

The lagoons are not the only poor element of this waste management system. Lagoon waste is eventually used as fertilizer, which means that gallons of hog waste are essentially sprayed into the air. This use of fertilizer results in runoff into local water sources, making many water sources unusable and harming the aquatic ecosystems. Besides the obvious air pollution, local communities have to deal with the noxious scent, with one Duplin county resident saying the manure “smells like a body that has been decomposed for a month.”

These issues with waste management have disastrous health effects. According to a 2018 study by the North Carolina Medical Journal, life expectancy is lower in North Carolina communities in the same zipcode of large industrial farms, even after accounting for other health factors. .

A Continued Pattern of Environmental Racism, and the Light at the End of the Tunnel

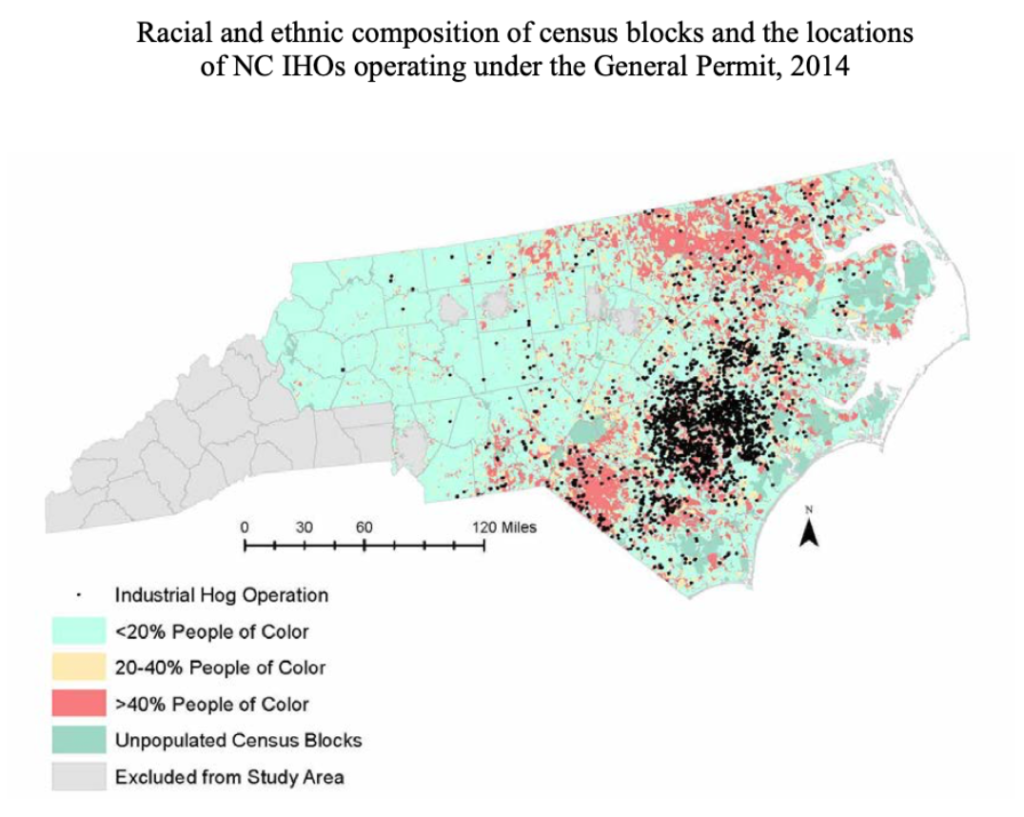

All of these impacts disproportionately affect low-income minority communities. A study by the Department of Epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found that the proportion of people of color within 3 miles of an industrial hog farm is 3.3 times higher than that of non-Hispanic Whites.

Despite the direct link between hog farms and lower quality of life, millions of dollars are devoted to silencing the voices within affected communities who speak out against these large industries. Large corporations like Smithfeild who run these farms stand as tough opponents because of their large economic and political presence in North Carolina.

However, the power of these industries has not stopped residents from coming together. In 2014, over 500 North Carolinians slammed Smithfield farms with over 24 federal lawsuits over the mismanagement of hog waste, claiming that Smithfield neglected their responsibility to properly dispose of manure.

It was not until November 2020 that a settlement was reached, with local residents involved in the suit receiving over half a million dollars. However, it is still unclear whether changes will be made to improve the hog waste management systems and the lives of the residents near these farms.

Silver Linings in Sustainable Solutions

The hog industry may seem like public enemy number one, but they are also the main source of economic activity for many small minority communities. This is why it is important for these industries to create more sustainable methods of operation, while still providing jobs and growth to these communities.

New solutions already exist that can help the hog industry continue to bring in the bacon while reducing environmental and health impacts for surrounding areas. Smithfield has started implementing a process where the biogases are captured from the lagoons and converted into extractable natural gas.

Smithfield Foods has released a statement that they will invest $500 million in implementing technologies by 2028, with the goal of becoming the largest natural gas supplier in the U.S. This could make a big difference — the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions would be equivalent to taking half a million cars off the road

Residents are still weary, and rightfully so. They would rather see alternatives to the lagoons, and have alleged that Smithfield is simply greenwashing: Putting on a facade of sustainability for publicity purposes. Local communities still worry about risks that the lagoons bring, and would prefer new methods of hog farming and waste management altogether.

While many speculate whether or not changes will be made to improve waste management, the lawsuit has put pressure on industries like Smithfeild that will certainly accelerate the development process of more sustainable ways to hog farm. Residents are finally being heard, and they are not going to stop at a settlement — they are going to secure their environment for generations to come.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The impacts of North Carolina communities’ fight against hog farming will not just be felt locally. In fact, it’s more than a national matter: China outsources a majority of its pork production to North Carolina, after which Smithfield sends approximately 300,000 tons of pork back to China.

However, while other regions and nations profit, it is the small Southern communities that are impacted by the billions of gallons of hog waste produced yearly. We must understand the environmental and equity implications not just behind pork, but around all of the meat products we consume.

As a North Carolinian myself, I am not asking you to give up your delicious pulled pork sandwiches. Instead, it’s time for us to speak out about these justice issues and shop more responsibly. Try to buy pork from local farmers, not factory farms, and limit your barbeques to special occasions.

Use your money and your voice so speak out against industrial hog farms. If local residents speaking out made a difference, imagine what national and even global support for these residents could do.