“Because I’m country!”

Said Catherine Coleman Flowers when asked why she was passionate about working for rural communities as an environmental justice advocate.

Growing up in the “Black Belt” region of Alabama, which is known for its rich dark soil, Flowers fell in love with the environment that enveloped her.

“I just loved nature and going for walks in areas where most people wouldn’t walk and picking plums and eating them off the plum trees,” she remembered.

But the term “Black Belt” also points to the history of slavery in Alabama. So, not only was Flowers surrounded by nature growing up, but she also grew up in a place steeped in southern history.

“Bloody Lowndes” Beginnings

Flowers was born in Birmingham and raised in Lowndes County, Alabama of the rural southern United States. Lowndes County was commonly referred to as “Bloody Lowndes” due to its history of racism and violence. The county also connected Selma and Montgomery—two cities instrumental in the Civil Rights Movement. But Lowndes County was especially known for importing and distributing enslaved people in the state of Alabama in the 1800s.

“The founders of Lowndes County actually came from South Carolina, and they brought their slaves with them and a lot of slaves were sold into the area. And my family, my father’s family, were descendants of those slaves that were in Lowndes County,” said Flowers.

The county itself was named after the enslaver, plantation owner, and U.S. congressman William Lowndes of the deep south.

Flowers grew up with this backdrop of racism and slavery from Lowndes County’s past, but also within an atmosphere of activism and community as a child of the Civil Rights era.

Some may say Flowers was born to be an activist. “I had a lot of influence from my parents who were activists, as well as those people who were around or would come in contact with my family. And they helped me to develop a sense of community, and a sense of responsibility of being able to provide the best for that community,” she said.

While she may not have realized it at the time, her parents and those they interacted with played instrumental roles in the Civil Rights Movement. From seeing the work that her parents did, activism was ingrained in her at a young age.

“My parents were kind of like the jailhouse lawyers of the community, everybody went to them to ask for advice. They helped a lot of people; they did a lot of organizing. These are things that were just second nature. It wasn’t anything special to me because that was what I saw at the time,” she said.

The Racial Violence That Led to Flower’s Activism

In her teens, Flowers remembered a transformational experience which played an integral part in her becoming an activist.

After her little brother was born at John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital, the same hospital which held the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis study, doctors purposefully sterilized her mother. Flowers noted this was something that not only happened to her mother, but other minority women at the hospital. Her mother went on to spend much of her life protecting other women from what had happened to her.

When the British Broadcasting Company, BBC, had come to interview her parents about their experience, Flowers learned of her own high school principal potentially being involved in the killing of a nine-year-old Black girl.

“There was a reporter who also anchored the NBC affiliate in Montgomery, he anchored the evening news, Black reporter, and he talked about my principal, and he said that my principal allegedly had been involved in the death of a young Black girl, nine years old,” said Flowers, “She was found with pajama bottoms wrapped around her neck and her body was found in a ditch. And [the news anchor] said that the principal allegedly was providing young Black girls to white men in Montgomery. And that struck me,” she explained.

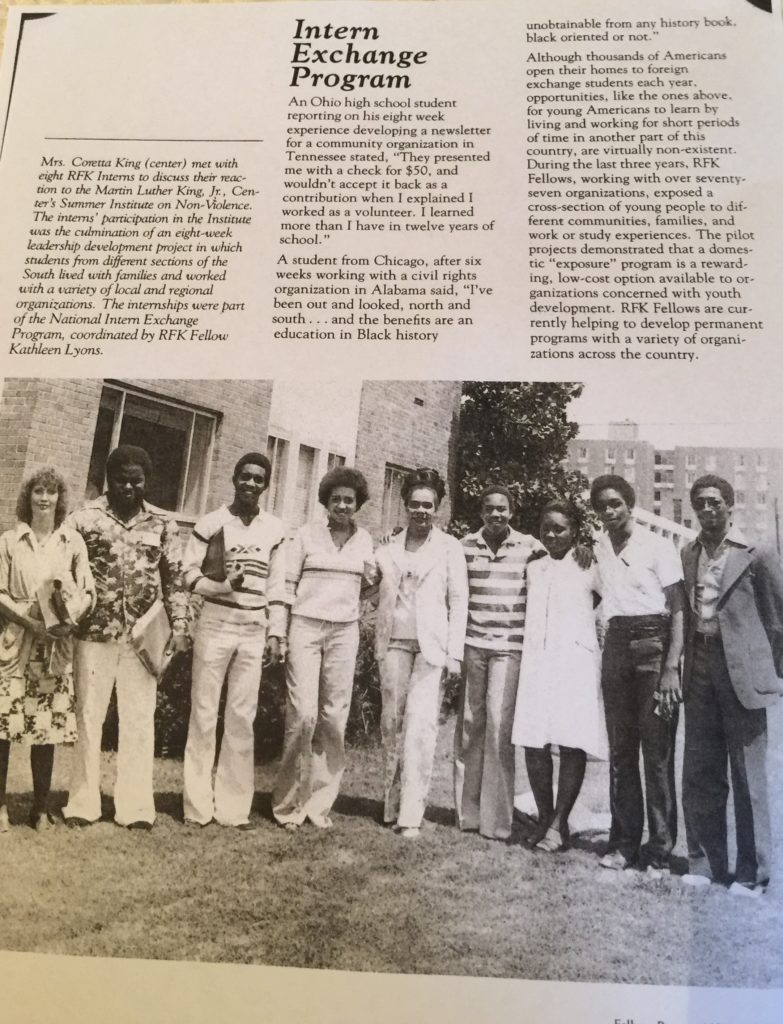

At the age of 16, she became a Robert Kennedy Fellow and worked to get rid of both her principal and the superintendent of the schools successfully, helping to protect the futures of Black children in Lowndes County. As a Fellow, she continued to investigate into what should and should not be happening in schools in terms of children’s safety, such as what had happened in her own school district.

Becoming an Advocate for Her Community on Climate Change and Raw Sewage

In her adulthood, Flowers became a teacher and often used the Civil Rights Movement to inspire the younger generations she was teaching. From her own experience as a youth activist, Flowers believes young people have more power than they realize.

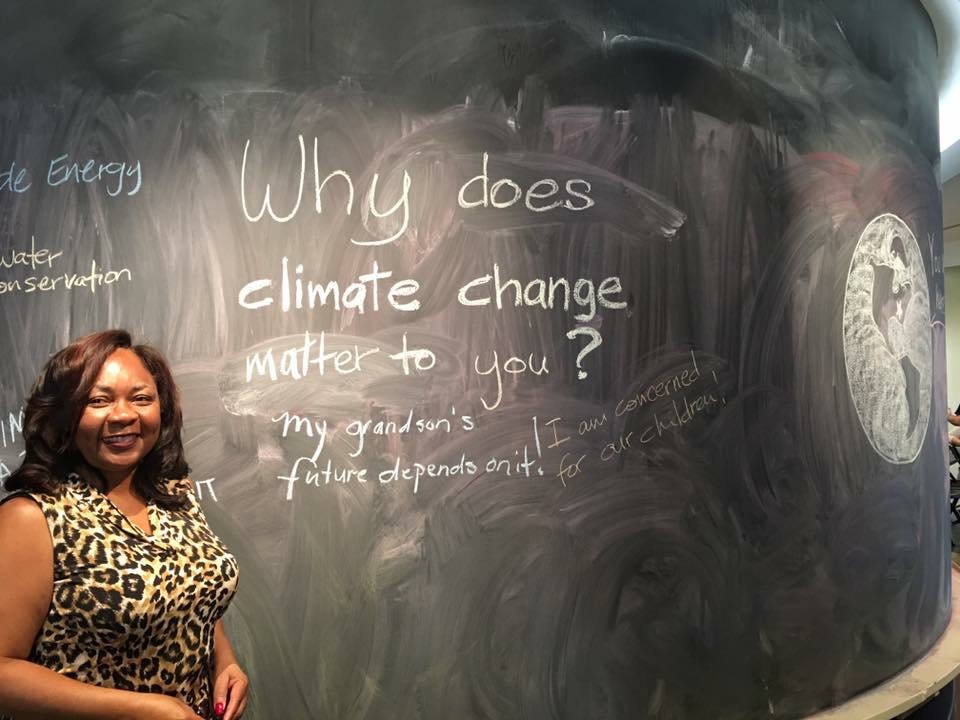

As a teacher, Flowers started realizing something was wrong. She felt the heat in cities like Washington, D.C. where she worked due to the heat island effect and started seeing animals from the south move to the north. She didn’t know what was happening until she watched “An Inconvenient Truth,” a documentary which discussed the horrors of climate change.

“When I saw the “Inconvenient Truth”, I was able to give it a name, and that was climate change,” she said, referring to the abnormal environmental problems she was witnessing.

Moving back to Alabama in 2000 to work on economic development in Lowndes County, Flowers began seeing wastewater issues in her own hometown. She would see pools of waste in people’s yards in the same places where kids would play. What was worse was that climate change was exacerbating these issues. But, the infrastructure to solve these problems for rural communities was almost nonexistent and proper wastewater management systems were blocked by an expensive paywall.

Flowers found that families were facing serious health problems as a result of the exposed waste. But she realized that doctors couldn’t provide a lot of solutions.

“Were there diseases that were manifesting in the U.S.? Because of climate change? I was alarmed because of the intersection of poverty, that American doctors were not trained to look for [these diseases] because they didn’t expect them to be here,” she wondered.

After partnering with the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Flowers and scientists worked together to find what was causing the mysterious health problems of Lowndes County residents.

Their study found that 34 percent of residents tested positive for hookworm, known as a disease of poverty, as a result of their exposure to raw sewage. The parasite is known to live in warm and moist climates and is especially common in places with poor sanitation.

Flowers discussed how many Americans do not realize the extent of poverty in the U.S. and how that results in poor sanitation and wastewater management. But, she struggled to show the true extent of the issue, which was rooted in systemic issues predominately impacting rural and impoverished communities.

“The biggest barrier, and keep in mind I’ve been doing this for at least 18 years, was helping people to understand and acknowledge that there was a wastewater problem in this country. That people do not have access to wastewater infrastructure. And it was not due to a personal failing. It was due to structures that were in place that prevented [access],” she explained.

Not only was Flowers angered, but she realized she had to do something about it. She asked herself, “If we can treat wastewater in outer space to drinking water quality, why can’t we do that here?”

Becoming a Leader for Rural Communities

Flowers soon founded the Alabama Center for Rural Enterprise, later reforming it into the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice (CREEJ). Addressing the intersections between environmental issues and poverty, CREEJ strives to create solutions that factor in the climate to solve wastewater management and infrastructure issues that are replicable elsewhere.

Flowers emphasizes that this problem is everywhere, “Everybody thinks it’s just Lowndes County. In the state of Alabama, it’s in all 67 counties. But, in just about every place in the United States, there is some problem, some form of wastewater issue,” she said.

Even more so, she wanted to become a voice for her fellow rural Americans.

“The other problem that I had initially with this work is that people don’t understand rural communities and I still run into that where people just make certain assumptions,” she said, going on to explain that people don’t understand the nuances and differences between rural and urban communities.

Flowers often sees legislation lacking a rural perspective, despite one in five Americans living in rural areas, states the U.S. Census Bureau.

“I think oftentimes when policies are written to deal with infrastructure, even to deal with climate change, it mostly is from an urban perspective. It leaves out the lack of inclusive language to address rural communities,” she continued.

Becoming an Author and Inspiring Future Generations

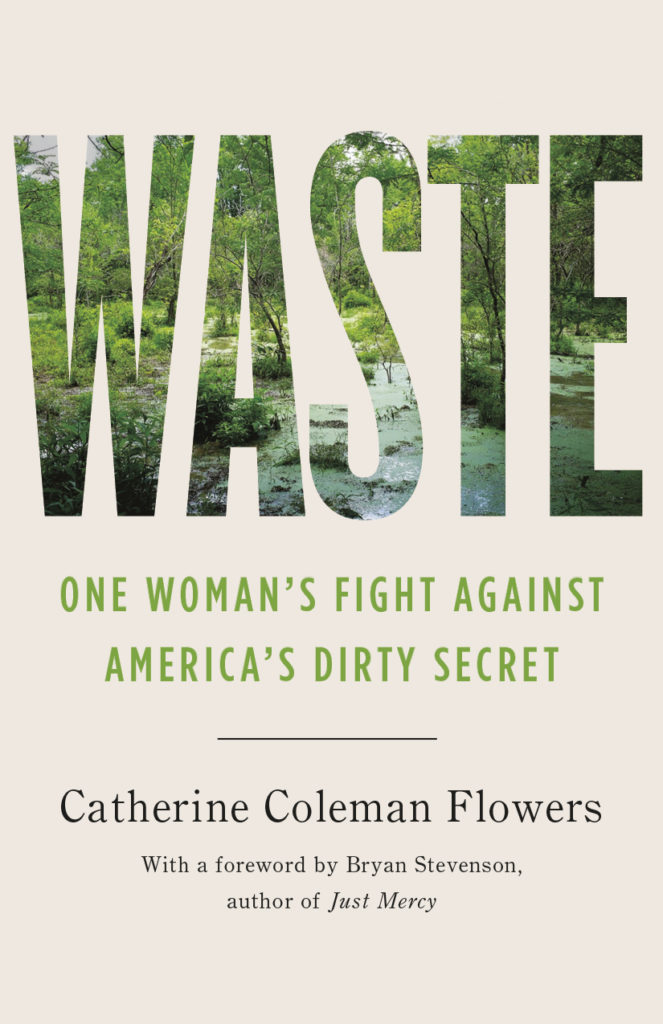

From her life and her work as an environmental justice advocate, Flowers believed it was time for all to hear her own personal journey and encourage others to take action to build a better, greener, and more equitable future for all. So, she started writing a book last year on her experience. Set to come out this November, Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret discusses how Flowers got to where she is today and why she chose to deal with the problems others chose to avoid, such as wastewater issues and climate change.

“I think part of the lesson I’ve learned is we can’t let people ignore it. If they ignore it, there will never be a fix,” she said.

Flowers wants her book to encourage others, especially youth, to take action.

“I want to inspire young people to carry on this fight without them having to start from square one. And the book documents my journey. By sharing it like that, it gives them an opportunity to see if they want to do this type of work, where they fit in, and how they can expand and to move it to the next level,” she explained

Through her book, Flowers hopes to become a source of inspiration for others just like many individuals had been one for her.

Hope for the Future

Recently, Flowers was one of only eight climate leaders to be selected to serve on Biden’s Climate Task Force. Being a country girl from “Bloody Lowndes” Alabama and now advising a United States presidential hopeful, Flowers has found that the support of those who are closest to her has helped her to achieve such success.

“I stand on a lot of shoulders. And I’d probably take up this entire interview just naming people who have been instrumental in influencing me from my childhood even through now,” she told me.

She emphasized her parents’ role in her activism. “I think what I developed from my parents was a sense of what is morally right and a sense of giving a voice to people that do not have the access, or the privilege themselves,” she said, hoping to use her platform to do just that.

While Flowers and those in her life and community have faced continual challenges, she remains optimistic.

“I am hopeful for the future because young people are the future… The fight, the vision, I see we are going to get closer to where we need to be.”

All photos courtesy of Catherine Coleman Flowers

Catherine Coleman Flowers was recently named to the Biden Climate Task Force, which has only eight members total. As an environmental justice activist from Alabama, Flowers founded the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice (CREEJ), working to solve wastewater sanitation issues by looking at how poverty and climate change intersects in the United States. She also serves on the Board of Directors of the Climate Reality Project and as Rural Development Manager at the Equal Justice Initiative. Additionally, she is a Duke University Franklin Humanities Institute Practitioner in Residence. Currently, she is writing a book titled Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret, hoping to inspire younger generations to take environmental action. The book will be released this November, published by The New Press.