Empathy & Equity outlines historical and modern flaws that leave marginalized communities disproportionately vulnerable in the face of climate change. In highlighting healthier solutions, E&E weaves environmental justice into the fabric of the environmental movement to create a more equitable planet.

When it comes to environmental justice, most of us automatically think of very visible problems like toxic waste or pollution. While these undoubtedly qualify, environmental injustices present themselves in various forms, many of them so imbued within our social structures that we fail to realize that they are environmental at all.

For this reason, the lack of access to affordable, nutritious food options in low-income communities — especially Black and Brown neighborhoods — is particularly insidious.

Food Apartheid — Not ‘Desert’

Food apartheid refers to systemic constrained access to healthy food sources. The phenomenon has garnered widespread publicity during the last three decades, where these areas are commonly dubbed ‘food deserts.’

To speak sustainably, leaders of food sovereignty movements urge us to retire this term. Not only does it water down food injustice to a matter of location — it erroneously implies that these areas develop from “natural” settlement patterns and that the people living within them are not invested in their own food sovereignty.

Apartheid, typically associated with the sanctioned racial segregation and discrimination against nonwhite people in South Africa, reaches the crux of the issue: Food insecurity driven by racial segregation and income inequality.

Apartheid reaches the crux of the issue: Food insecurity driven by racial segregation and income inequality.

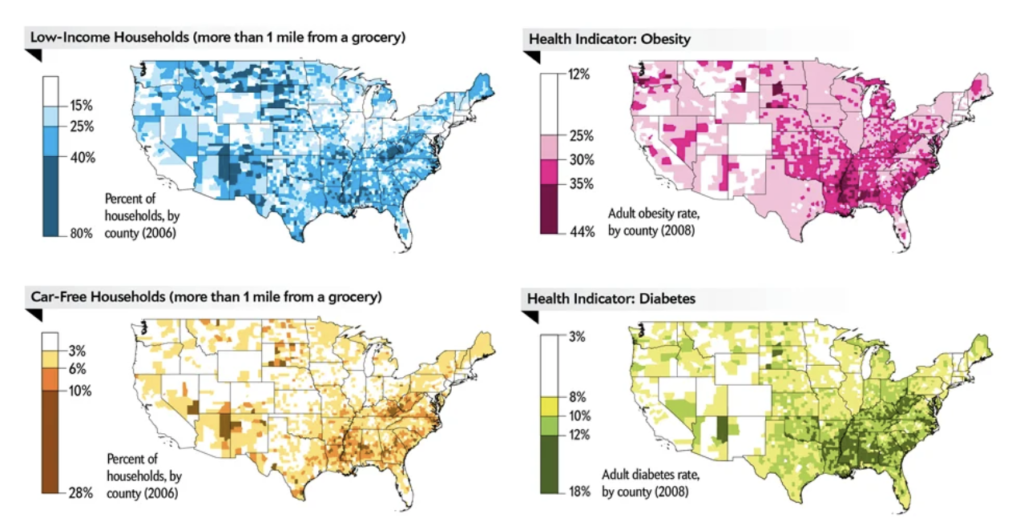

The U.S. Department of Agriculture distinguishes places experiencing urban food apartheid as low-income areas with at least 33% of the population living 1.0 miles or more from the nearest supermarket. The threshold is slightly farther for low-income rural communities at 10 miles.

It is important to note that lack of access in rural communities often stems from poor transportation infrastructure rather than racial segregation and income inequality. For this reason, urban food apartheid is the focus of this blog post.

Instead of grocery stores, urban low-income areas are permeated with fast food restaurants, liquor stores, and convenience stores. In fact, the density of fast food businesses in a neighborhood is inversely related to its average household income: As income goes up, the prevalence of fast food restaurants goes down.

This relationship was not formed by chance — it is the culmination of hundreds of years of systemic oppression, and discussions of its implications must be situated within the historical context of urban sprawl.

Urban Sprawl

Urban sprawl is a pattern of metropolitan growth in which low-density, automobile dependent, exclusionary new developments (like suburbs) are built on the fringes of deteriorating cities.

Post-war North America underwent large scale economic restructuring throughout the latter half of the 20th century. As manufacturing jobs declined, service jobs surged in their place, many of them high-paying positions in finance, communications, and law.

Downtown facilities were constructed to accommodate well-paid professionals during the workday, after which they returned to their homes in the outlying suburbs. As a result, these downtown and suburban locations saw rapid economic development while urban residential neighborhoods deteriorated.

Sprawl is intimately intertwined with race. People of color, especially Black people, experienced growing wealth and income discrepancies after the economic shift because they were excluded from many of these high-paying positions and the informal social networks where job placements were made. As jobs migrated to the suburbs and became even harder to find, the concentration of poverty in urban areas grew in a mutually reinforcing cycle.

Poverty was exacerbated by white flight, the mass migration of white families out from cities to avoid living in racially diverse neighborhoods “in decline.” As white families left, they took their generational wealth with them, adding to the lack of resources and investment in inner city communities.

The discrepant quality of urban neighborhoods and their suburban counterparts penetrates all aspects of life to the modern day — including food. Food apartheid functions based on two dimensions, price and distance, both of which invoke unjust hardship on the people within its grasp.

Drivers of Food Apartheid

Distance

Whole Foods. Trader Joe’s. Target. Drive through any predominantly white, middle- to high-income suburban area and you’ll see at least one of these chains within minutes. Conversely, the American Journal of Preventive Medicine reports that predominantly Black, urban neighborhoods in the U.S. have a quarter the supermarkets of white neighborhoods.

Predominantly Black, urban neighborhoods in the U.S. have a quarter the supermarkets of white neighborhoods.

It follows that access to healthy, affordable food within these communities is contingent on access to a private vehicle or public transportation. But, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the percent of people affected by food apartheid without access to a vehicle is 24 to 38 percent higher than in other urban neighborhoods.

At the same time, low-income urban neighborhoods tend to be more car-reliant than their wealthier counterparts because of a lack of sufficient public transport systems. Without access to a vehicle or public transit, people within these areas are constrained to local food selections — at a price.

Price

People living through food apartheid not only face spatial barriers against accessing healthy food sources — they also pay higher prices. Urban residents pay between 3 and 37 percent more than their suburbanite counterparts for the same products.

Why? As supermarkets continue to migrate to the suburbs due to urban sprawl, residents of urban communities are forced to rely on local stores with smaller selections — stocked with less fresh produce and more processed food — at higher prices.

Since food apartheid is concentrated in low-income neighborhoods, this price discrepancy often dictates what residents are willing to buy. A case study of Seacroft, a British authority housing state ranked among the most deprived 1% of England, found that women with young children overwhelmingly shop based on cost, electing to purchase frozen beef burgers over more expensive cuts of fresh meat.

While cheap, processed foods cost less money, they incur a different expense over time: Health.

Health Consequences

Systemic limitation to nutritious food has serious health consequences — higher rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other diet-related conditions are documented in low-income and minority communities than the general population.

But people of color, particularly Black, low-income populations, may also encounter medical racism — systemic discrimination that favors white physicians and white patients — as they seek treatment for diseases onset after prolonged exposure to urban food apartheid.

The result is a negative feedback loop: Constrained access to healthy food driven by racial inequality causes diseases, which are dealt with in hospitals, where Black people risk receiving inadequate care due to more racial inequality.

This loop became even more pronounced during the pandemic, when global food insecurity has skyrocketed because of higher prices and reduced incomes. We need solutions now more than ever, and it’s more than a matter of funds.

More Than a Matter of Funds

Divestment in Black and Brown communities is not a matter of insufficient government funds: It’s a matter of where the funds are going. Politicians continue to hike spending for policing and incarceration in Black communities while reducing spending for public education, housing, and healthcare. Ironically, these very investments in public health and well-being would accomplish politicians’ purported goals of crime reduction.

Divestment in Black and Brown communities is not a matter of insufficient government funds: It’s a matter of where the funds are going.

What would investments in public well-being look like? Rebuilding public transportation infrastructure, implementing incentives for food retailers to move into low-income neighborhoods, and introducing mobile markets are just a few solutions for improving food access in inner-city communities.

Youth education is another crucial avenue toward establishing food sovereignty. Along with offering nutritious lunch options, schools should teach students about oppressive food regimes and foster action early on, such as encouraging students of color to pursue futures in agriculture.

What Climate Communicators Can Do

The first step toward ending food apartheid is realizing that it’s happening. Many white people harbor misconceptions that racial segregation is a thing of the past, absolving them internally from their role in perpetuating it.

Recognizing that historical context is always at play — whether it be where we live or the foods we have access to — positions us to treat the disease of racism itself, rather than the symptoms.

If you live in an area impacted by urban food apartheid, prompt discourse with other members of your community about what it means and avenues for change, like growing food locally. Working with local retailers or writing to public officials are other ways to garner support.

The Journey Continues

Truly ending urban food apartheid requires nations to address the structural and institutional racism that spawned its existence. This involves intricacies that I encourage you to analyze through the works of people who know them best. Below are a few of the many resources written by Black environmental justice advocates on the intersection of race and food:

- Black Food Geographies: Race, Self-Reliance, and Food Access in Washington, D.C. by Ashanté M. Reese

- The Color of Food: Stories of Race, Resilience and Farming by Natasha Bowens

- Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement by Dr. Monica M. White

Now that we’ve dipped our toes into the vast pool of environmental injustices, our journey toward environmental Empathy and Equity continues with a deep dive into the meat industry. Stay tuned, folks — we’re just getting started.

Someone necessarily lend a hand to make critically articles I might state.

That is the first time I frequented your website page and thus far?

I amazed with the analysis you made to make this particular publish extraordinary.

Excellent job!

Hi, after reading this remarkable article i am as well happy to

share my knowledge here with mates.

Hi there, I enjoy reading all of your post. I wanted to write a little comment to

support you.

May I just say what a relief to discover someone who actually

understands what they’re discussing over the internet.

You actually realize how to bring an issue to light and make it important.

More and more people have to check this out and understand this side of

the story. I was surprised that you’re not more popular given that you surely possess the

gift.

Its such as you read my mind! You seem to grasp a lot about this, like

you wrote the e book in it or something. I feel that you can do with

some p.c. to force the message house a bit, but other than that, that is great blog.

An excellent read. I will certainly be back.

Hi everyone, it’s my first visit at this web page,

and paragraph is really fruitful in favor of me, keep up

posting these content.

I am not sure where you are getting your information, but good topic.

I needs to spend some time learning more or understanding more.

Thanks for magnificent information I was looking for this information for my

mission.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.