Nature-based experiences and education can be the key

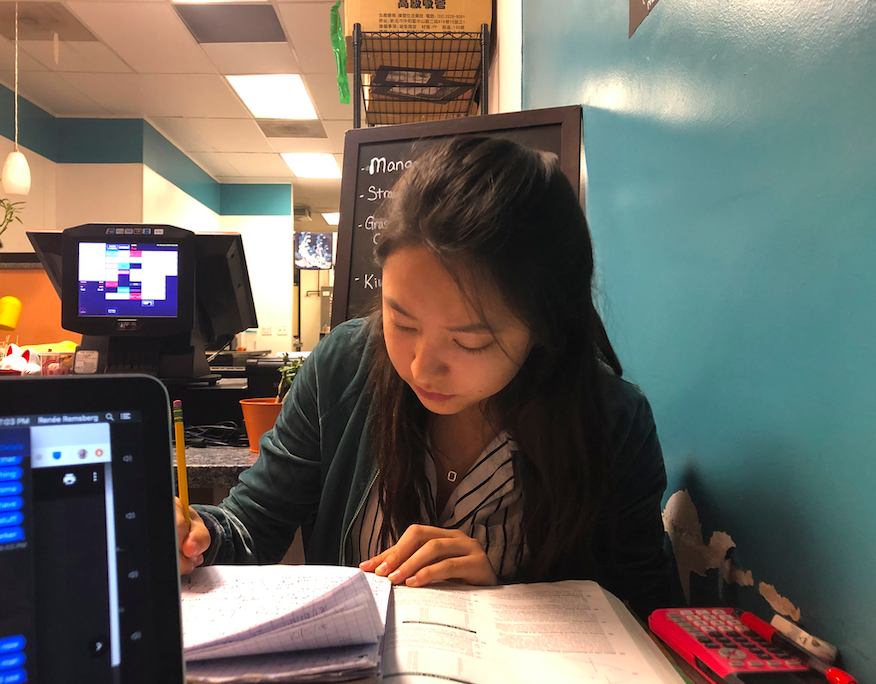

I wiped an escaped tear away, half-covering my face in the semi-darkness of my AP Environmental Science class. As bleached coral reefs, struggling marine species, and concerned researchers flashed on the projected screen, I felt absolutely overwhelmed by the sheer amount of terrifying imagery. I felt the weight of this slow, impending tragedy called climate change as a second, third, and then a storm of silent tears streamed down my face. And all the while, my classmates sat around me, talking and Snapchatting, entirely apathetic.

In all of my years in the American education system, I have never taken a required environmental course. I, however, have been luckier than most. The school district that I attended had nature-based field trips. As a small child, I was whisked away to zoos, aquariums, and state and national parks. In particular, trips to Yosemite and Pigeon Point in California first enchanted me with the outside world. Enormous trees! Amazing rock formations! Gorgeous bluffs, and a lighthouse to boot!

To my younger self, these trips were invaluable; they kicked off my environmental journey. I immediately felt a connection to the planet and all of the gorgeous places and the life on it. The stunning amount of natural beauty the world contained was (and is) unfathomable and awesome to me — it absolutely beat all of the time spent indoors poring over multiplication tables and pronoun-antecedent agreement worksheets.

“The impression that our planet left on me was enormous — Mother Earth had stretched her arms, enveloping me, aiding me in finding comfort.“

The impression that our planet left on me was enormous — Mother Earth had stretched her arms, enveloping me, aiding me in finding comfort, respect, and absolutely no fear in nature. In grade school, whenever I had an opportunity to choose a subject for a particular project, I always found a way to bring it around to environmentalism. Tectonic plates in fourth grade? I dove into the slow erasure of Peruvian beaches. Eurasian geography in fifth grade? I explored soil erosion in Azerbaijan. Engineering in sixth grade? I theorized about a device that could extract greenhouse gases and CFCs from the atmosphere.

Part of why I think I so determinedly pursued environmental topics was because any lesson in school surrounding the planet felt half-hearted and incomplete. Sure, my eighth grade class dived into ocean acidification in basic chemistry, but not once were the actual effects of that acidification on marine ecosystems described. My middle school most definitely emphasized the importance of reducing, reusing, and recycling, but the three Rs have been outdated for years, and we were never taught about how recycling centers in our city could not even process half of the plastics we were tossing into blue bins.

As I entered my senior year of high school, the effects of Gen Z’s hands-off environmental education began to show. The lack of any foundational environmental knowledge in my peers was all the more glaring, in that kids my age didn’t realize the stunning danger the climate crisis represents.

That year, I proudly chose to take AP Environmental Science, a real class that would focus on ecology and our species’s impact on the environment. But most of the teens in my class took the course as a joke. AP ES was the easiest AP class around — a verifiable GPA booster. My classmates would snicker through conversations about renewable energy sources and toxic waste disposal. While I was tearing up during a documentary about the slow but steady loss of our planet’s coral reefs, my peers were on their phones.

“The disconnect between human beings and our environment grows and grows.“

The disconnect between human beings and our environment grows and grows. We separate ourselves from the elements, ridding our concrete homes of any and all specks of dirt. We work ourselves hard, driving to and fro to make ends meet, having little time left for self-care, friends, and family, let alone for fostering a connection to the planet.

It’s no wonder that most Americans (and most people worldwide) do not fully understand the realities of our climate crisis. The climate crisis is a silent one, but our everyday problems are loud. Environmental and ecological alterations happen slowly over time — temperatures rise a few degrees every few decades and our air becomes a little more polluted each year — but our rents are due every month, food must make it to the table every day. It’s hard for us to personally find balance in all aspects of our lives, but at the same time the slightest changes in the environment unfortunately tip the internal balance of our planet, eradicating our environmental homeostasis.

In this way, environmental education, both scientifically- and socially-based, should be directly woven into our national education system. A class that puts together the pieces we are introduced to in chemistry and biology should be grounded by societal impacts, illustrating the very real, very imposing, very threatening reality of the effects of climate change and our direct roles in exacerbating this crisis.

School and family forays into nature were what allowed me to create my initial connection to the planet, but I was privileged to have those opportunities. So how can we listen to our environment when the climate crisis is silent and our lives are so loud?

Only by imbuing in rising generations an appreciation for nature and its preservation can we truly guarantee a world for future generations to live on. Only by creating a foundational level of environmental knowledge in the general population — through our national education system — can we begin to understand all that our planet does for us and what we should do for ourselves and our planet.

It is absolutely integral to our survival.