Paging Earth is a climate communications blog dedicated to demystifying, depolarizing, and educating the public about climate change activism and climate science.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, our world has shifted dramatically — for some more than others. Despite all of the distractions and problems we are all facing right now, climate change has not been put on pause. Climate change continues to harm us all — but especially marginalized communities all over the world, alongside our planet.

It is crucial that climate communicators spread the word about climate action and encourage education on environmental justice. However, stigmas and assumptions laced within our words can inhibit effective education.

How we speak about environmental topics — from sustainability to advocacy to climate change awareness — impacts political and personal actions in more ways than one. The language of sustainability must echo rhetoric that cherishes the planet and the health of its communities. With the right mindset, a path to communicating about these topics in a positive and productive way will reveal itself.

The Language of Conflict

War metaphors are all over the media, bolded on the headlines of political journals, news stations, and even science publications. The “fighting climate change” mentality assumes that opposition and conflict are the best way to make progress. Sure, it does encourage a sense of urgency and combats feelings of apathy. But where does this language lead us?

Hostile and war-based language has catalyzed retrograde for climate communicators and the general public consensus on ‘the battle against’ climate change. It is invaluable that we, as climate communicators and members of society, consider the words that we use when we speak about the future of our planet and its communities — and what emotions and reactions they provoke.

Discrepancies in climate action support are likely the result of the media focusing on conflict and opposition suggested by a study focusing on psychological blocks in bipartisan climate policy. After all, there is always a winner and a loser in war.

It makes sense why language of this sort provokes a partisan mentality. But does it limit our ability to solve problems as a collective? Unfortunately, yes. If climate change is a war, then we are all losing together. But it’s not too late.

Decolonizing Climate Language: Speaking with Lakota Wisdom

Shifting our words away from war-based language is a vital step for productive communication. Indigenous perspectives provide valuable insights on how to communicate with the right mindset.

Indigenous communities across the world are often targeted for the lands they live on and the resources they have access to. Their voices widely remain unheard. Even in the Paris Climate Agreement, Indigenous communities, their lands, and protection of culturally significant sites were not referenced whatsoever.

Tatewin Means — an Indigenous woman from the Sisseton Wahpeton Dakota, Oglala Lakota, and Inhanktonwan nations in South Dakota — notes that many words are rooted in “colonizer concepts” in the series Climate Curious.

Reclaim the power. Assert your power. Ownership. These phrases are commonly used in a climate and social justice context by activists. But what realities do they convey beneath the surface? While advocating for “power” and “ownership” appears to be rooted in good intention, this language is entrenched within a larger, problematic mindset.

Colonizer language encourages power-centric attitudes in regards to the Earth and our neighbors, which inevitably leads to inequity in the global community. As Tatewin says, “With power comes control, and when one is focused on gaining control someone is always going to be without.”

In order for healing to occur for BIPOC communities, colonizer concepts must be weeded out of climate justice language. Language like property ownership and land control, for example, reinforce the power structure of colonialism from which these communities aim to break free. Redefining “wealth” is also a necessary paradigm shift because western values and ideologies continue to impose upon these communities.

What do we all need to start owning? Our responsibility. Our duty to take care of ourselves, our planet, and each other. Language such as “responsibility,” “stewardship,” and “sovereignty” resounds tones of more hopeful, respectful language toward the Earth and its communities.

Fostering hope and respect for the planet is crucial. As humans, we are only one piece in a massive puzzle of living things in a balanced, earthly community. From a Lakota perspective, land is not a possession. It is a gift and resource to be respected and cherished, as are our relationships with each other as relatives of the Earth. Imagine if all shared such a perspective as a common mindset — how different would our world be?

Tatewin echoes this wisdom: “We are all relatives in this global community. This is not simply a liberation struggle for Indigenous communities, but a liberation struggle for everyone. White Americans have to decolonize. We need to press a reset button on how we think about these things in relation to the broader community. That is not just people, it is all beings on this earth.”

We need to press a reset button on how we think about these things in relation to the broader community. That is not just people, it is all beings on this earth.

Tatewin Means

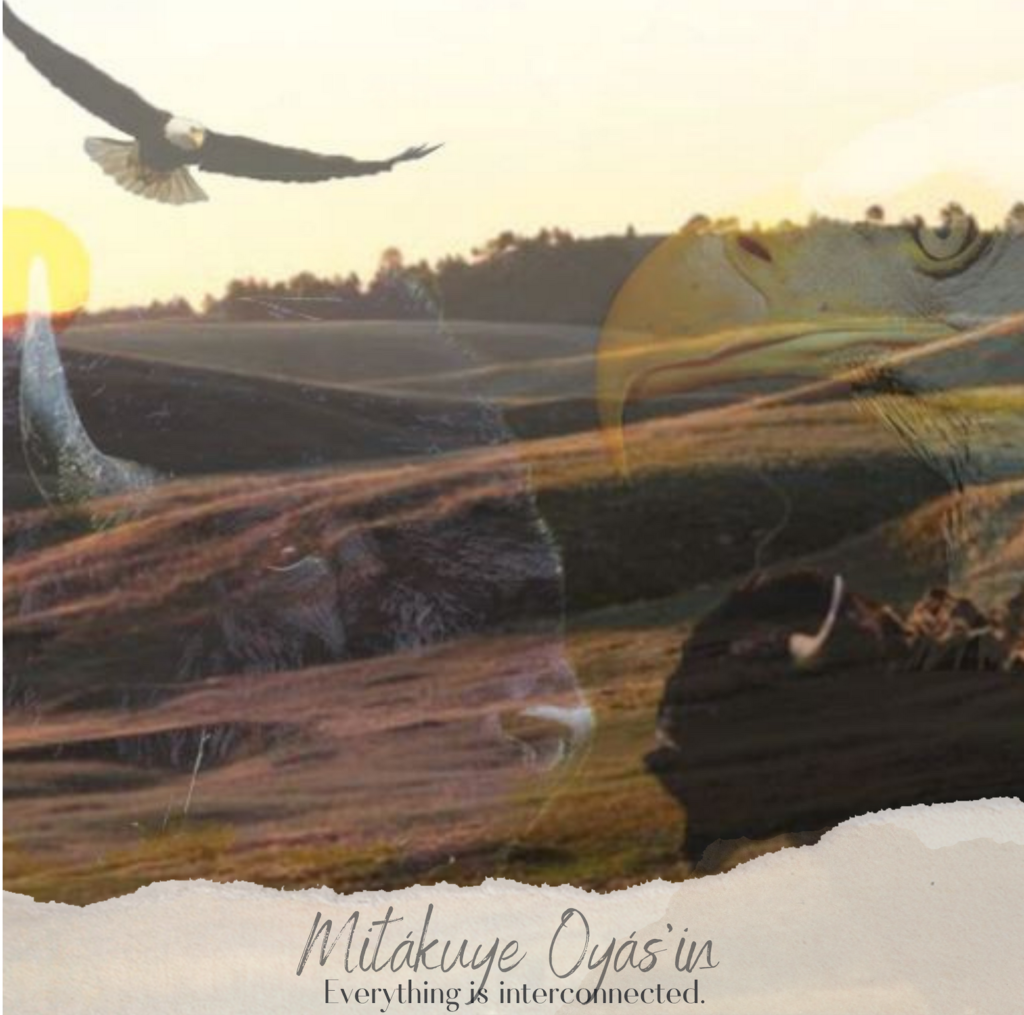

Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ (All Are Related) is a phrase from the Lakota language. Everything is interconnected.

How can we liberate ourselves from this mindset?

Liberation starts within before it can ripple outward. Oglala Lakota activist Russell Means shares his insight on decolonizing our language and mind in his bestselling call-to-action autobiography, Where White Men Fear to Tread:

“One is expected to know things, to believe things. Knowing and believing are all in your head – there is nothing in your heart…You will find it easy to believe that we as humans are the dominant species, and to act as though the Earth and everything on it are ours to do with as we please. That is not so.”

Russell Means

Consider your heart when you speak and when you act. We must use our language to emulate the heart’s connection to the Earth for not only healing, but also to manifest the necessary, peaceful, hopeful mindset for climate action and world citizenship.

How can we support Indigenous communities?

- Listen, and create an avenue for voices to be heard.

Communicating effectively also takes the knowledge of when to listen. Step back and make room for voices from historically marginalized communities to be heard. Essential BIPOC voices continue to be excluded from this conversation. Environmentalism is unfortunately white-dominated, and more diverse voices must be added to the choir.

- Educate yourself and be careful to not turn Indigenous peoples into a monolith.

Learn about the Indigenous history of the land where you live or where you are from. Ask yourself: Where are these communities today, what happened to them, and why? How can I support them?

There are thousands of Indigenous communities around the world. They do not share the same, monolithic worldview — be intentional and aware of how you use the term “Indigenous” to describe tribal wisdom.

- Amplify sustainable language.

More than listen, we all must spread the message and communicate the wisdom of these communities using intentional, sustainable language. As a rule of thumb, always try to avoid words and phrases that echo tones of conflict and opposition. For example, we can reframe phrases like “the battle of climate change” and “fighting against climate” to “addressing climate”, or “working with climate”. Focus on phrases and words that promote healing, respect, stewardship, and interconnectivity. These changes might seem small, but will carry tones of togetherness and positivity across the movement which are invaluable in this time sensitive journey towards healing.

- Donate and provide support to Indigenous organizations.

Share their message and goals, and create awareness for their needs.

Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation is an indegnous non-profit organization that seeks liberation of Lakota people through language, lifeways, and spirituality.

Return to the Heart Foundation is a grantmaking organization empowering visionary Indigenous women led initiatives.

First Nations Development Institute improves economic conditions for Native Americans through direct financial grants, technical assistance & training, and advocacy & policy.

Climate change is happening now, and to all of us, but the impacts will not be equal. Justice is at the forefront of environmentalism, and places a responsibility on every single one of us to contribute to change.

Remember that we are all a piece of the puzzle, and our words, too, have a role to play. And embracing the interconnectedness of all things is one very important step for us to take for the betterment of the planet we all call home.

Sources

Means, Tatewin and Sarah Eagle Heart, directors. Climate Curious: Episode 3 – Indigenous Liberation. Youtube, The Solutions Project, 14 July 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=juwA-Dci8zs.

Grist, Kate Yoder for. “To Take on Climate Change, We Need to Change Our Vocabulary.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 16 Dec. 2018, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/dec/15/to-take-on-climate-change-we-need-to-change-our-vocabulary.

“Native Sun News: Author Brings Lakota Heritage to Stewardship.” Indianz, www.indianz.com/News/2015/017247.asp. Accessed 25 Mar. 2021.

NoiseCat, Julian Brave. “The Western Idea of Private Property Is Flawed. Indigenous Peoples Have It Right | Julian Brave NoiseCat.” The Guardian, 27 Mar. 2017, www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/mar/27/western-idea-private-property-flawed-indigenous-peoples-have-it-right.

Means, Russell, and Marvin J. Wolf. Where White Men Fear to Tread: the Autobiography of Russell Means. St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

“Environment | United Nations for Indigenous Peoples.” Un.org, 2018, www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/mandated-areas1/environment.html.