Empathy & Equity outlines historical and modern flaws that leave marginalized communities disproportionately vulnerable in the face of climate change. In highlighting healthier solutions, E&E weaves environmental justice into the fabric of the environmental movement to create a more equitable planet.

Zip code matters more than genetics when it comes to quality and length of life. Alarmingly, cities mere miles apart can have a 30 year discrepancy between the average lifespan of residents. Along with factors like pollution and healthcare, this disparity is driven by access to green spaces.

What are Green Spaces and Why Should We Care About Them?

Green spaces are natural environmental areas typically used for recreational or aesthetic purposes. If you’ve ever strolled through your local park, stopped to admire a public garden, or utilized a greenway, you’ve enjoyed a green space.

The benefits of green spaces are numerous. Along with supplying ecosystem services — or environmental benefits like fresh air — places to exercise, and aesthetic beauty, they provide tree cover and vegetation. This decreases air pollution and mitigates the urban heat island effect.

Not only are green spaces important for balancing ecosystems; they make us healthier. Spending as little as two hours in nature every week predicts better health and well-being, including improved cognitive performance, less mental fatigue, and reduced mortality.

Unfortunately, access to greenery is considered a privilege in our society — one that is not bestowed equally. Green space varies by zip code, with factors like race and income playing a dominant role in predicting access.

Pieces of a Recurring Puzzle to Access

Like many environmental injustices, disparities in green space are intersectional, meaning that multiple forms of discrimination overlap. In this case, the main forms are racism and classism. As we piece together why these disparities exist, we must consider how the two interact in order to see the big picture.

Race

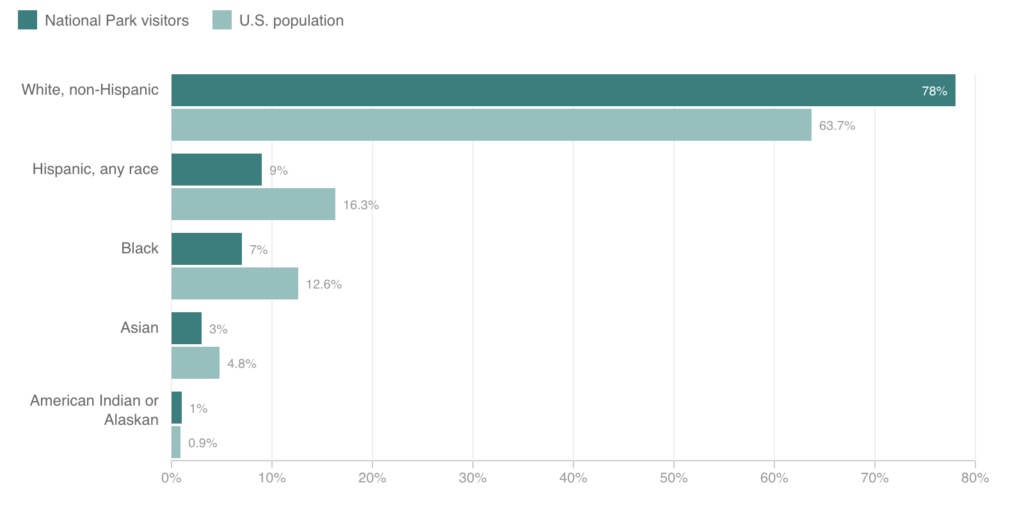

Given that the United States was founded under the regime of white supremacy, it is unsurprising that its parks were, too. People of color, particularly Black Americans, were “legally barred from, or segregated at, public recreational sites, including national and state parks” until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Compounding this racial discrimination is the violence that Black people and other people of color have endured in national parks and outdoor spaces for centuries. This historical context permeates the present: As of 2009, 16 percent of African Americans report that they have never visited a national park due to safety concerns.

Moreover, data collected by the U.S. National Parks Service from 1982 to 2016 revealed that Latinx and Asian people comprise 5 percent of national park visitors, while Black people make up a mere 2 percent.

And it’s not just national parks. To this day, Black and Latinx neighborhoods have significantly less local green space than their white counterparts.

Systemic discrimination incurs a cost. Remember the heat island effect? One study found that red-lined communities are the hottest neighborhoods in 94% of U.S. cities — a disturbing consequence of historically racist urban planning policies.

In addition to being hotter, concrete jungles offer less opportunities for exercise and fresh air, contributing to the long-documented higher rates of obesity and related illnesses among Black and Latinx populations.

Income

It is important to note that variations in green space do not always follow a straightforward racial inequality paradigm. Income and education are the missing pieces of the puzzle, with economic status being a key predictor of access to green space.

Essentially, wealthy neighborhoods have more parks, and these parks are bigger and better tended. In fact, the average park size in wealthy New York urban neighborhoods is more than twice that of poor urban neighborhoods.

This pattern holds true in London, where the wealthiest neighborhoods have about 10 percent more public green space than the most deprived areas, where about half of residents are minorities.

Historically, parks were a luxury reserved for the white and the wealthy. Consequently, less affluent areas — many of which experience systemic divestment in public resources — have been neglected by urban planning policies for incorporating green space. These policies, coupled with years of racial discrimination from outdoor recreational spaces, spawned harmful stereotypes that people of color do not belong in nature.

If you’re beginning to see parallels between predictors of access to green space and predictors of other environmental injustices, you are not alone. Time and time again we have seen that white, wealthy, educated people fare better at the expense of marginalized communities, rendering these communities more vulnerable to disasters like COVID-19.

Seeking Solace Outside: COVID-19’s Impact

Mandatory quarantines during the pandemic nudged many folks, including myself, to seek solace outside. Walks around the neighborhood and backyard hangouts became staples as families across the globe coped with social distancing, inadvertently re-establishing starved connections to nature.

But that privilege was not universal. One in three Americans — over one hundred million people — do not have a park within a 10-minute walk from home. In New York City alone, 1.1 million people did not live within a 10-minute’s walk from a public park during quarantine. Amidst the stress of a pandemic, imagine the physical and mental effects of that green deprivation.

The implications are in the numbers. Black and Latinx Americans — populations that experience inequitable access to green space the most — are both approximately three times more likely to be hospitalized and twice as likely to die from COVID-19 than white Americans.

An antidote to this disparity? Green spaces. Neighborhoods with higher ratios of green space reported lower racial disparities in COVID-19 infection rates even when controlling for other factors like income, evidencing the protective health benefits of time spent in nature.

COVID-19 starkly revealed that access to green space can be, quite literally, a matter of life or death. And in the face of climate change, the stakes have never been higher.

High Stakes, Higher Responsibility

As temperatures rise with climate change, the role of green spaces in mitigating heat is more crucial than ever. The heat island effect in communities without precious tree cover and vegetation will be magnified, disproportionately harming people of color and low-income neighborhoods.

Environmental racism is “the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on people of color.” Contrary to popular belief, environmental hazards encompass more than just waste and pollution — they are any condition that adversely affects the environment and human health.

Disparate access to green space is environmental racism at work; the effect of white people’s historical exclusion of people of color from outdoor recreational areas lingers. Environmental justice — which mandates ethical land use, the reconfiguration of cities and rural areas to be in balance with nature, and fair access to resources — cannot be achieved without addressing inequitable green space based on race and income.

The time to act is now. As climate allies, we turn to organizations that facilitate access to green space for inspiration and guidance.

Rooting for Change

The impacts of access, or lack thereof, to green spaces are undeniable. As a result, strategies to alleviate these inequities have already begun taking root. In 2020, Public Health England released a 112-page report dedicated to improving access to green space. Among their recommendations are integrating public health teams in the planning and development of green spaces and supporting local programs for social engagement in nature.

One such program, Outdoor Afro, builds Black connections and leadership in nature through hikes, expeditions, events, and workshops. Founded by Rue Mapp as a blog in 2009, the nonprofit has since grown into a nationwide effort with leaders in 42 cities.

The representation and access promoted by organizations like Outdoor Afro are critical for dismantling racial stereotypes that make Black people and other people of color feel like they do not belong in nature.

Expanding the Definition of Nature

In cities that have already developed extensive infrastructure, building large swathes of new green areas may not be feasible. Fortunately, similarly health-boosting greenery can also be integrated through green infrastructure in schools, workplaces, and homes.

Green infrastructure, or networks of multifunctional green space, comes in various forms. Establishing green roofs on buildings, pockets of vegetation, or rain gardens are a few examples of ways that cities can weave greenery into the fabric of daily urban life.

As Emma Marris theorizes in her TED Talk “Nature is Everywhere,” our current definition of “nature” as sites untouched by humans is misleading and outdated — after all, more than half of the world’s population lives in urban areas. Instead, she advocates for us to view nature as anywhere where life thrives, whether that be urban streams, wild meadows, or a city park.

If we are to move forward with Marris’ definition, governments must better integrate green spaces and green infrastructure into all neighborhoods, reducing inequities that allow some groups to thrive more than others. This involves supporting and consulting local organizations that cater to the green needs of their communities. Subsidizing environmental education and trips to national parks in schools are other steps toward ensuring green spaces are accessible to all.

As individuals, recognizing inequities in green space is an important first step toward meaningful change. From there, I encourage you to pursue concrete actions like donating to local organizations promoting access to green space in underserved communities. Signing our Global Climate Pledge is another powerful way to demonstrate your commitment to mitigating climate change and defending communities that will be affected the most.

For too long, low-income and predominantly non-white neighborhoods have faced barriers against the benefits of outdoor spaces. If you have access to green areas, use your voice to advocate for others who do not. We must act as if lives depend on it — because they do.